Krebs - E-Verify’s “SSN Lock” is Nothing of the Sort

One of the most-read advice columns on this site is a 2018 piece called “Plant Your Flag, Mark Your Territory,” which tried to impress upon readers the importance of creating accounts at websites like those at the Social Security Administration, the IRS and others before crooks do it for you. A key concept here is that these services only allow one account per Social Security number — which for better or worse is the de facto national identifier in the United States. But KrebsOnSecurity recently discovered that this is not the case with all federal government sites built to help you manage your identity online.

A reader who was recently the victim of unemployment insurance fraud said he was told he should create an account at the Department of Homeland Security‘s myE-Verify website, and place a lock on his Social Security number (SSN) to minimize the chances that ID thieves might abuse his identity for employment fraud in the future.

According to the website, roughly 600,000 employers at over 1.9 million hiring sites use E-Verify to confirm the employment eligibility of new employees. E-Verify’s consumer-facing portal myE-Verify lets users track and manage employment inquiries made through the E-Verify system. It also features a “Self Lock” designed to prevent the misuse of one’s SSN in E-Verify.

Enabling this lock is supposed to mean that for the next year thereafter, if an unauthorized individual attempts to fraudulently use a SSN for employment authorization, he or she cannot use the SSN in E-Verify, even if the SSN is that of an employment authorized individual. But in practice, this service may actually do little to deter ID thieves from impersonating you to a potential employer.

At the request of the reader who reached out (and in the interest of following my own advice to plant one’s flag), KrebsOnSecurity decided to sign up for a myE-Verify account. After verifying my email address, I was asked to pick a strong password and select a form of multi-factor authentication (MFA). The most secure MFA option offered (a one-time code generated by an app like Google Authenticator or Authy) was already pre-selected, so I chose that.

The site requested my name, address, SSN, date of birth and phone number. I was then asked to select five questions and answers that might be asked if I were to try to reset my password, such as “In what city/town did you meet your spouse,” and “What is the name of the company of your first paid job.” I chose long, gibberish answers that had nothing to do with the questions (yes, these password questions are next to useless for security and frequently are the cause of account takeovers, but we’ll get to that in a minute).

Password reset questions selected, the site proceeded to ask four, multiple-guess “knowledge-based authentication” questions to verify my identity. The U.S. Federal Trade Commission‘s primer page on preventing job-related ID theft says people who have placed a security freeze on their credit files with the major credit bureaus will need to lift or thaw the freeze before being able to answer these questions successfully at myE-Verify. However, I did not find that to be the case, even though my credit file has been frozen with the major bureaus for years.

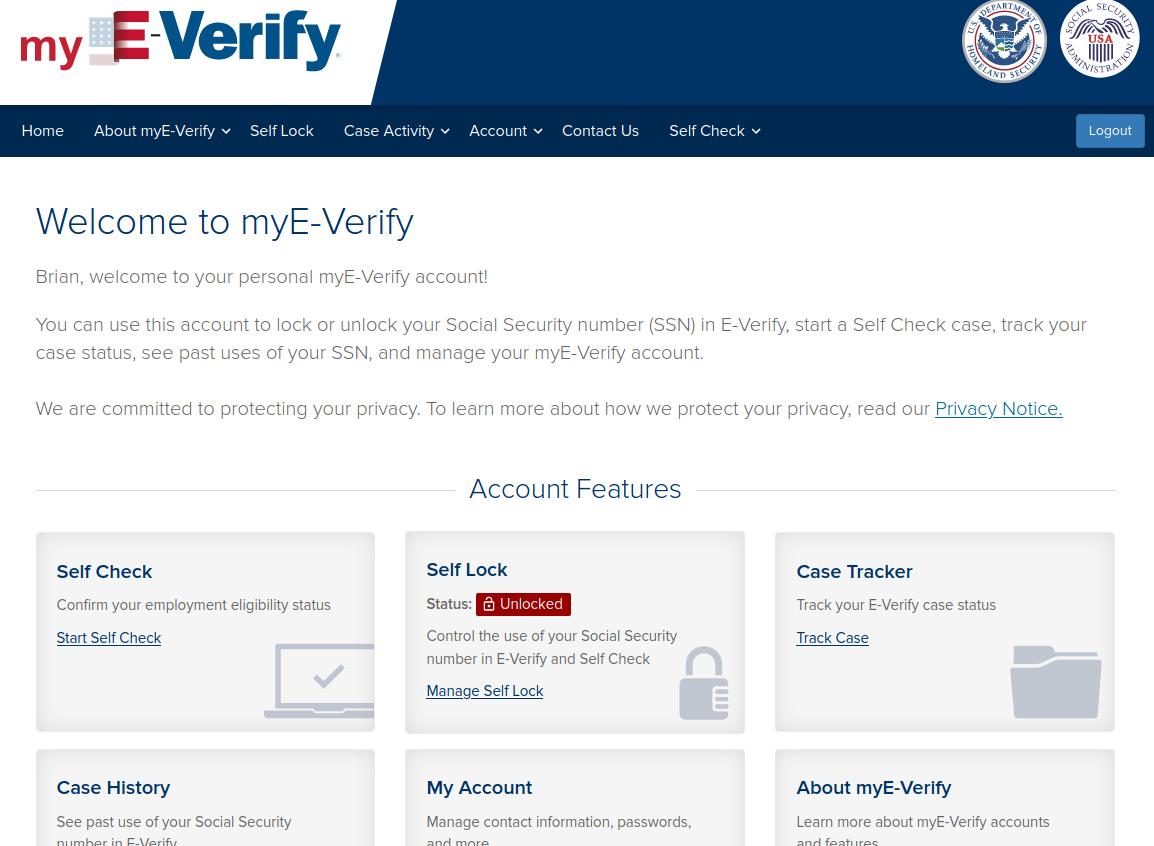

After successfully answering the KBA questions (the answer to each was “none of the above,” by the way), the site declared I’d successfully created my account! I could then see that I had the option to place a “Self Lock” on my SSN within the E-Verify system.

Doing so required me to pick three more challenge questions and answers. The site didn’t explain why it was asking me to do this, but I assumed it would prompt me for the answers in the event that I later chose to unlock my SSN within E-Verify.

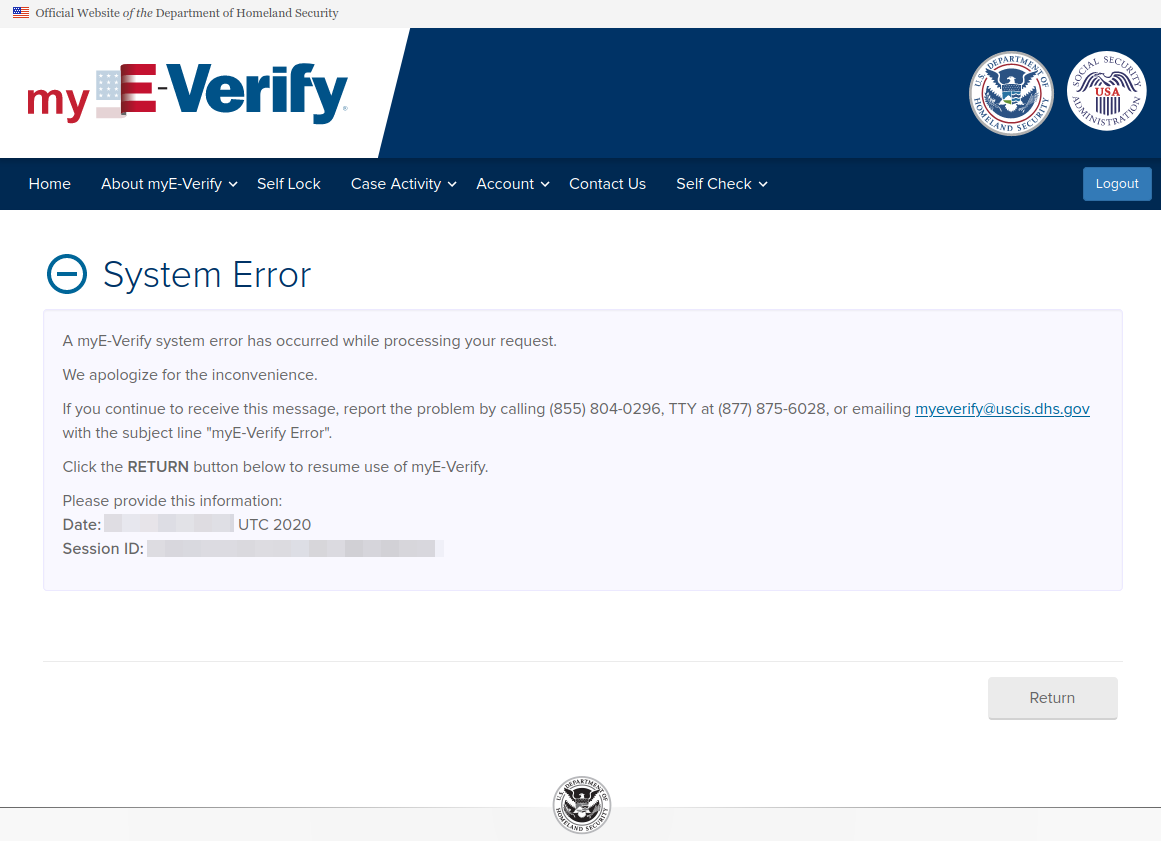

After selecting and answering those questions and clicking the “Lock my SSN” button, the site generated an error message saying something went wrong and it couldn’t proceed.

Alas, logging out and logging back in again showed that the site did in fact proceed and that my SSN was locked. Joy.

But I still had to know one thing: Could someone else come along pretending to be me and create another account using my SSN, date of birth and address but under a different email address? Using a different browser and Internet address, I proceeded to find out.

Imagine my surprise when I was able to create a separate account as me with just a different email address (once again, the correct answers to all of the KBA questions was “none of the above”). Upon logging in, I noticed my SSN was indeed locked within E-Verify. So I chose to unlock it.

Did the system ask any of the challenge questions it had me create previously? Nope. It just reported that my SSN was now unlocked. Logging out and logging back in to the original account I created (again under a different IP and browser) confirmed that my SSN was unlocked.

ANALYSIS

Obviously, if the E-Verify system allows multiple accounts to be created using the same name, address, phone number, SSN and date of birth, this is less than ideal and somewhat defeats the purpose of creating one for the purposes of protecting one’s identity from misuse.

Lest you think your SSN and DOB is somehow private information, you should know this static data about U.S. residents has been exposed many times over in countless data breaches, and in any case these digits are available for sale on most Americans via Dark Web sites for roughly the bitcoin equivalent of a fancy caffeinated drink at Starbucks.

Being unable to proceed through knowledge-based authentication questions without first unfreezing one’s credit file with one or all of the big three credit bureaus (Equifax, Experian and TransUnion) can actually be a plus for those of us who are paranoid about identity theft. I couldn’t find any mention on the E-Verify site of which company or service it uses to ask these questions, but the fact that the site doesn’t seem to care whether one has a freeze in place is troubling.

And when the correct answer to all of the KBA questions that do get asked is invariably “none of the above,” that somewhat lessens the value of asking them in the first place. Maybe that was just the luck of the draw in my case, but also troubling nonetheless. Either way, these KBA questions are notoriously weak security because the answers to them often are pulled from records that are public anyway, and can sometimes be deduced by studying the information available on a target’s social media profiles.

Speaking of silly questions, relying on “secret questions” or “challenge questions” as an alternative method of resetting one’s password is severely outdated and insecure. A 2015 study by Google titled “Secrets, Lies and Account Recovery” (PDF) found that secret questions generally offer a security level that is far lower than just user-chosen passwords. Also, the idea that an account protected by multi-factor authentication could be undermined by successfully guessing the answer(s) to one or more secret questions (answered truthfully and perhaps located by thieves through mining one’s social media accounts) is bothersome.

Finally, the advice given to the reader whose inquiry originally prompted me to sign up at myE-Verify doesn’t seem to have anything to do with preventing ID thieves from fraudulently claiming unemployment insurance benefits in one’s name at the state level. KrebsOnSecurity followed up with four different readers who left comments on this site about being victims of unemployment fraud recently, and none of them saw any inquiries about this in their myE-Verify accounts after creating them. Not that they should have seen signs of this activity in the E-Verify system; I just wanted to emphasize that one seems to have little to do with the other.

from Krebs on Security https://krebsonsecurity.com/2020/07/e-verifys-ssn-lock-is-nothing-of-the-sort/

Comments

Post a Comment